How does emotional validation affect us?

Comments Off on How does emotional validation affect us?This article is part of our current series explaining what to expect from different forms of therapy that we deliver at JSA Psychotherapy.

It’s sometimes tricky to understand what we can do with our emotional experiences or even whether there IS anything we can do with them. Emotions are often invisible, and we use a lot of abstract and theoretical ideas when talking about them. It can be helpful to think about a metaphor instead.

Imagine you have a high energy dog that you have to take on a long car journey. In the past, this dog has chewed bits of furniture and made a mess of the car. The most effective thing we can do is take the dog on a walk before the journey, to burn off as much of its energy as possible.

By exercising our dog, we can help it feel calm, rested, and relaxed. Of course, in order to exercise the dog, we need to notice that it’s full of energy, seeming excited or stressed. If we don’t notice, we can’t do anything about it.

Now imagine instead of a dog, we’re talking about a child. If you want a child to sleep well or relax, one of the best ways to do this is to tire them out by doing activities or exercise to burn off all their excess energy. Again, in order to do this, we need to notice that it’s needed or that the child isn’t feeling themselves.

Now, what if we noticed that the child is distressed so we decide to exercise them by taking them on a walk. All the way round, they keep complaining but we keep walking. At the end of the walk, they are still distressed and not relaxed or relieved. The best thing to do would have been to listen to what they were saying was distressing them.

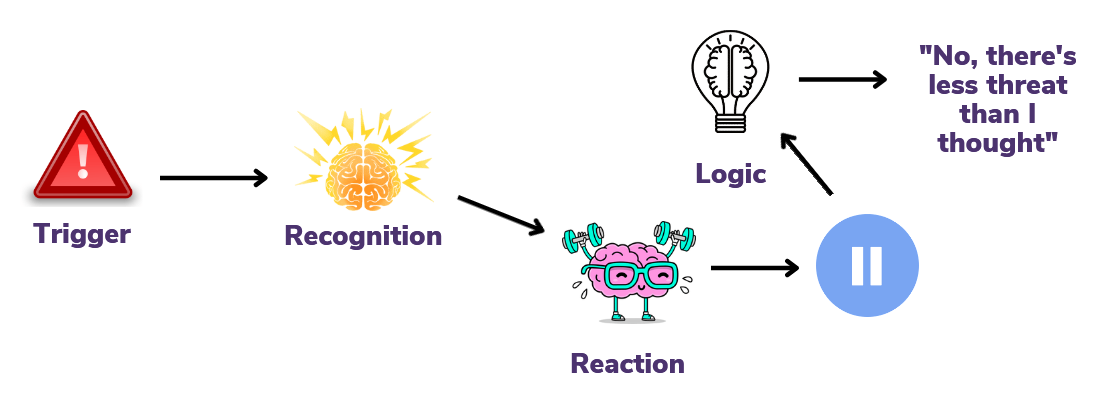

In several ways, our emotions are like that child in the previous example. In order to do what we need to do to be productive, we have to exercise those emotions. In order to know how to do that most effectively, we need to know what those emotions are telling us. In order to listen to them, we need to notice that they’re there.

This process is called ‘self-validation’ and is something that you have an absolute right to.

The difficulty is that, sometimes, people in our past didn’t notice our emotions and needs. Or if they did, they didn’t listen to what they were. Or if they did, they didn’t take them seriously and help us exercise them in a healthy way. This is called ‘invalidation’. If people do this enough, we think ‘oh that must be the way the world works, I’d better do that too’ and start to invalidate our own emotions.

If we start to invalidate our own emotions, we may think that they are unacceptable, weak, overwhelming, bad, daft, too much for us to manage, over dramatic or something similar.

IF THAT WERE TRUE, we would HAVE TO ignore, reject or downplay our emotions or even have a go at ourself if we do feel them.

If we’re rejecting our feelings, we can’t notice, listen to or exercise them so we end up with a lot of high energy emotions inside of us which makes it harder to do what we need to.

What if it wasn’t true though?

In 1983, group of scientists including a man called McKay ran studies which found that every human on the plant has a set of emotional rights. These included the right to feel and express your emotions and pain.

This means that we’re allowed to have emotions, allowed to notice them, allowed to listen to what they’re trying to say and allowed to exercise them.

Of course, it’s worth asking, ‘what’s the most effective way of exercising our emotions?’ What’s the way that works best? In deciding this, we have to remember that everyone is different, so the details of this answer will be worked out together with your therapist. But as a principle, we can say that it can be useful to

1. Do something to burn the energy that comes along with an emotion

2. Express the things you discovered when listening to the emotion (if words aren’t your thing then finding music which expresses it, doing a drawing/painting or other creative options work just as well) and

3. Doing this in a safe place without other people so you have the time and space to do what you’ve got to do.

It is a good and healthy thing to exercise our emotions, much more sustainable than silencing them. In order to do this, we need to notice when they have become activated and listen to the messages they give us.

Notice, Listen, Exercise

If you would like to download an info sheet version of this article as a pdf for your own use, you can do so by clicking this link.